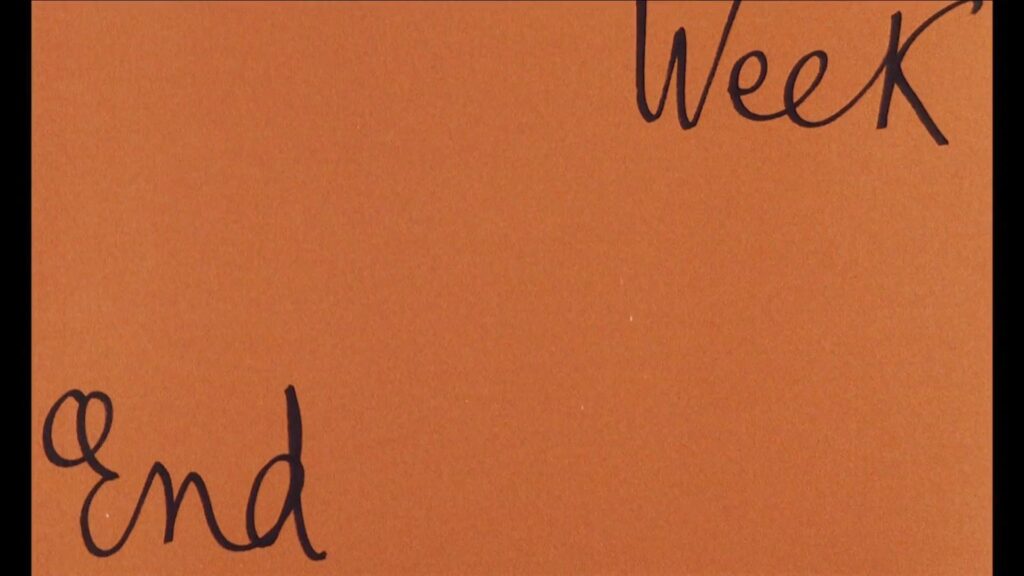

Few directors have been more influential on cinema than Jean-Luc Godard. And few films have been more influential than his 1967 black comedy Week-end. Week-end is a film with little narrative, few plot points, and tons of style.

Every frame of this film is brimming with expert craftsmanship. The blocking is unparalleled, whether it be newly found characters in a forest or lines of cars in an epic, minutes long unbroken dolly shot, and it is all executed perfectly. It’s a movie that’s lewd, provocative, and at times shocking so much so that the audience has no choice but to be thoroughly engaged throughout despite the lack of a traditional plot or macguffin propelling the movie forward.

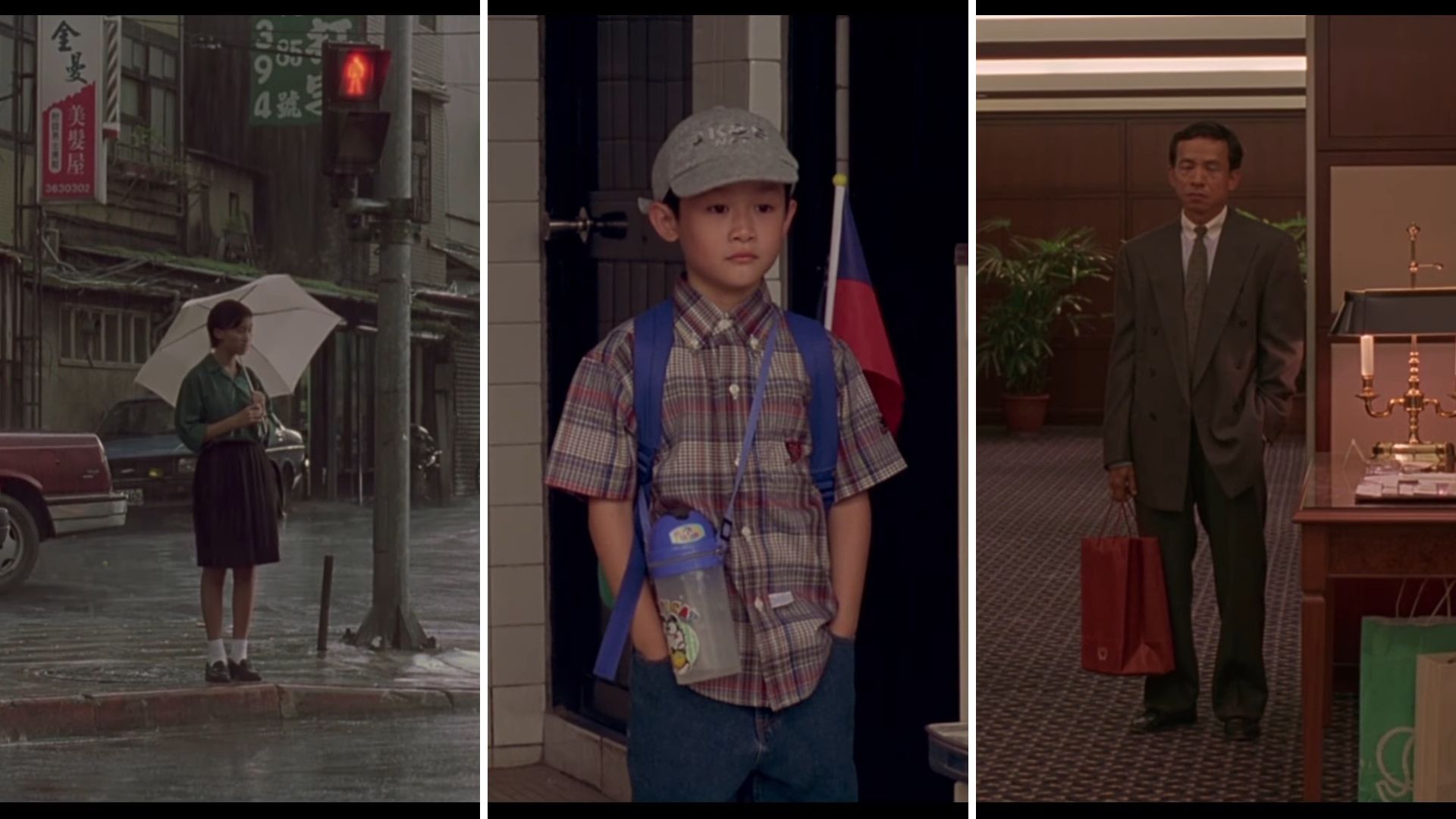

Greed

The basic thread of the plot involves Roland and Corrine. A middle-class couple who each conspire with their separate lovers to murder each other for financial gain. This, though, is really just a set dressing for the themes and ideas Godard wants to convey in his film. While the movie begins with a noir or thriller-type setup with each couple secretly conspiring behind the others’ backs to murder and take their money, the movie quickly devolves into a comedy of errors in the French countryside.

Along their trip, they run into every class of society, numerous vehicle accidents, and even some famous figures. Everything in this film is just a metaphor. The car crashes, the famous literary characters, and the multitude of social classes all work to tell an idea rather than a story. In a lesser film, these ideas would drag or come off as pretentious. But Godard has such a handle on his ideas, themes, and most importantly, technical artistry, that the whole thing works in a way that few films could ever replicate.

Lewd

Rather than try and go through the beats of the story, I’d rather just focus on some of my favorite parts of the film. Some of the reasons why I think it’s a masterpiece and why it is so well regarded by other industry artists. The first is a scene early on in the film where Corrine describes a dream, or something more, to an unknown man.

The scene is lit in a dim room with both characters almost appearing without color at first. The scene is scored with high-pitched strings in menacing tones. It’s a lighting and scoring choice that immediately makes the audience feel uncomfortable. The lack of comfort continues as she explains in clinical detail the lurid details of her most recent tryst. A threesome involving everything from a strategically placed egg to a saucer of milk.

The scene here is brilliant for a few reasons. The blocking, the way each character is placed, is intimate but clinical. The way Corrine, played by Mireille Darc, speaks is also devoid of any emotion. She explains so matter-of-factly every lewd and lurid detail to an equally unfazed man. This was the 60s. A time of drugs and free love. But still, the lack of emotion is alarming, and also a perfect set dressing for the next hour and a half of the film.

Horns

The next scene I want to talk about is obviously the famous traffic jam scene. This is a scene I’ve seen a few times, and truthfully, I hated it the first time I saw it. Not because I didn’t enjoy or appreciate the artisty, but because I hate car horns.

I won’t go on an extended rant about the use of horns and how the worst people on the planet overutilize this invention. But I will point out that this entire, nearly seven-minute-long scene is almost nothing but car horns. It’s an unbroken tracking shot that is visually fascinating to see. But an absolute chore to hear.

Traffic Jam

With the volume muted, I watched this scene a few times on this recent re-watch. I wanted to try and gather everything happening in the scene. To truly understand what Godard is trying to portray. And I think my muting the scene, detaching somewhat from what is going on, is exactly Godard’s purpose.

This entire scene, this long traffic jam Corrine and Roland move through, is all about detachment. We see tons of different things playing out during this scene. There’s an older couple playing chess on the side of the road, a caravan of animals, and buses emptied of people, all waiting in the same line of cars. Shooting this scene unbroken aside from full-frame title cards also keeps us fully in line with the mundanity and annoyance of the traffic jam.

At the end of the jam, Corrine and Roland pass by the cause of the jam. A brutal accident with bodies and blood spilled across the street. It’s a gory, shocking image that comes at the end of a comically long shot. But no one, least of all our leads, seems to care. They, like me with the car horns, are so annoyed by the whole ordeal, they just speed on by. Like everyone in this crazy world Godard has made. A world of greed and consumerism. These two only care about themselves and their destination. They are utterly detached from the mayhem and horrors happening around them. It’s a powerful metaphor executed with incredible artistry.

The Forest

The last scene I want to talk about comes at the end of the film and is another long take. After Corrine and Roland go on their exodus, they end up captured by a group of radicals and taken to the forest. This group has resorted to violence, anarchy, and cannibalism in order to survive. It’s a representation of the breakdown of society. A society that Corrine and Roland have been detached from throughout the whole film. So detached that they didn’t even notice society was crumbling around them.

The scene I love is right after they are captured. The camera stays planted, capturing three different subjects. A man playing drums. A nude person stretching in front of a tent. And a group of captives being taken into frame. The camera then slowly moves, revealing the captives being taken to a butcher. He’s told by a supposed leader what he can do with the woman before he cooks her, and then he’s off.

This scene reinforces both the idea of a collapsing society and also the detachment that’s been rampant throughout. This new world that’s formed, a new regime, is still just as detached as the wealthy and middle-class folks who plunged them into it.

The End of Cinema

Jean-Luc Godard is a master filmmaker, and Week-end may be his boldest project. He ends the film with the words “The End of Cinema” to denounce the then-current state of films. Godard was done with normal narratives, macguffin-driven plots, and easy-to-figure-out mysteries. He wanted his work to mean something. He wanted it to say something. And it did.

Week-end is an amazing film and one worth studying. It shows even now how comfort leads to detachment. Being able to live in a comfortable world, having the ability to afford nice things, and not worrying about basic needs, leads to a lack of empathy. A detachment from the world around you. So much so that you may not even be able to see when the world finally begins to crumble.