Robert Bresson’s 1959 film Pickpocket is a masterpiece of subtle storytelling. The film centers on Michel, played by Martin LaSalle, and his slow rise into a life of crime. This film is tremendously influential with its minimalist filmmaking techniques and close-up shots of technical blocking scenes.

Pickpocket is a slow burn and one that audiences and critics struggled with at the time. Bresson’s earlier film, A Man Escaped, was a larger, more epic narrative and in many ways follows the opposite of Pickpocket. A Man Escaped is a daring film about a man escaping from a Nazi prison where pickpocket, follows Michel as he makes his way to confinement. This didn’t resonate with audiences at the time, but over the years has found an audience that truly realized the genius of Bresson.

Confinement

I like to view Pickpocket as a companion piece to A Man Escaped. In that film, Fontaine, the main protagonist based on the real life prisoner André Devigny, begins the film in a Nazi prison. He slowly and methodically plans his escape by studying the guards and loosening the wooden boards of his cell. Throughout the course of the film, he devises a plan and eventually succeeds in escaping the prison. Finally able to leave the world of confinement behind him.

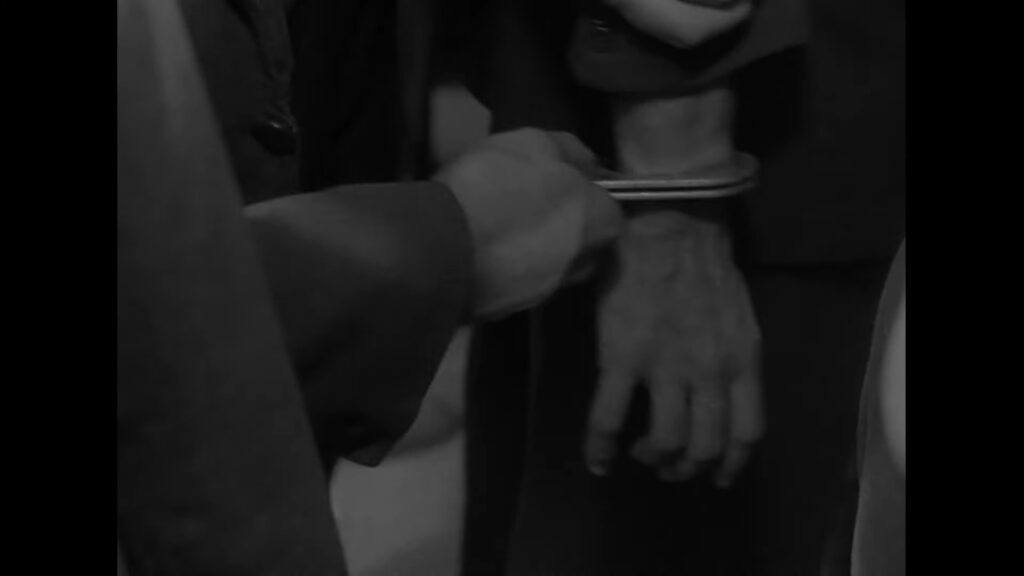

Pickpocket begins with Michel as a free man. He starts learning the ins and outs of basic thievery. Pickpocketing unknowing civilians for personal gain. He eventually teams up with some unsavory characters who help him master his skills. Michel has worked successfully for years, scamming and stealing from various people around France. He is arrested earlier in the film but is let go due to a lack of evidence. The arresting officer, though, continues to follow Michel, waiting for him to slip up. He finally does and is arrested on the spot, and the film leaves Michel imprisoned for his actions throughout the film. A Man Escaped ends with freedom, while Pickpocket ends with incarceration.

Freedom

All of this comes back to the big ideas and themes of Pickpocket. We see a man slowly fall deeper and deeper into a life of crime. It’s a life he’s forced into out of exasperation, and one he can’t find a way out of. Once he’s in this world, this life of crime, there’s no way for him to stop. Both for the monetary benefits and for the rush of the crime.

These themes and their influences can be seen in many films made decades later. One film that I felt had a huge connection to Pickpocket is the 2001 film Requiem for a Dream from Darren Aronofsky. That film is a little less subtle with its themes of addiction, but it follows four different people who fall further and further into their addictions until it eventually destroys them. It’s a film that, much like a Pickpocket, ends on a dour note. Even though these films end in tragedy, we can’t help but root for the protagonist. We want each one to get better, but we know they simply can’t. Their circumstances and addictions have brought them to a place they can’t escape from. And Robert Bresson doesn’t give them a happy ending. He doesn’t create a big spectacle or make any grand statements. He just shows us with technical perfection the life of a thief.

Spectacle

Where Pickpocket sets itself apart is with this minimalistic and subdued style of filmmaking. Pickpocket is filled with tight close-ups of pickpocketing. It’s truly masterful to see on film these intricate rube golberg type schemes being pulled off by Michel and his crew. The camera is able to perfectly capture each steal in a way few filmmakers would be able to.

Many films about crime do not have the restraint to pull off what Besson is able to. These films, movies like Heat or Point Break, can only show off heists in spectacular fashion. These are the selling points of those movies, and it’s what audiences come for. But with Pickpocket, we see the slow, methodical con starting to take shape. We see the hours Michel spends, taking a watch off a leg post, learning to hone his craft, only for the few seconds it takes him in real life to nab a real watch from an unsuspecting civilian’s wrist. Even though it’s subdued and subtle, it’s just as thrilling watching these brief little cons.

Legacy

Pickpocket had a tremendous impact on film, and we can see this film’s DNA everywhere from 70s masterpieces to current blockbusters. Besson follows one man. A troubled man who gets by the only way he knows how. He never has a redemption arc, and instead is forced to pay for his crimes.

Paul Schrader has often commented on the influence this film had on Taxi Driver. Martin Scorsese’s 1976 film is about a man who is also an outcast from society and forced to come to terms with the changing world around him. Taxi Driver is a bit more dreamlike, but each of these movies forces the audience to be with a lead character we don’t really like. We can’t relate, but we want them to be better. It’s a filmmaking and writing technique that leads with empathy. Something that is becoming more and more rare in cinema now.

Empathy

In the story of Michel, we see a man who has committed terrible acts. He abandons his sick mother, ostracizes his friends, and steals from innocent people. But throughout the whole film, we feel empathy for the character. We start to see his situation the same way he does. As one with no way out.

The last shot of Pickpocket is Michel in prison, reaching his hands through his prison cell bars and grasping the hand of Jeanne. The only person who seems to have truly cared for his well-being throughout the entire film. And he realizes that maybe what he was searching for, what he’s been reaching out for this whole film, wasn’t money or someone else’s wallet, but it was a companion. It’s a heartbreaking ending, but one that truly sums up the entire theme of the film perfectly in one shot. A feat only a filmmaker like Besson could pull off.