Tobe Hooper’s seminal 1974 film The Texas Chainsaw Massacre turns fifty this year. The film has gone on to spawn numerous sequels, several reboots, and even video game franchises. The main family of killers, including Leatherface, have become cultural touchstones in horror cinema. Its creation and success are remarkable if not a little confounding.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was made on a minuscule budget, with no-name actors, and a sensational premise. It was a gorefest movie with no gore. A rebuking of the meat industry set in Texas. This film had no business being successful but fifty years later it remains one of the greatest triumphs in horror cinema.

From The Grindhouse to The Slaughterhouse

In 1968, the Hayes Code, a self-imposed guideline of acceptable content for films, was all but abandoned. This, combined with advancements in filmmaking technology, allowed for movies with shocking violence or nudity, to be produced for cheap and have the opportunity to turn a profit. Many of these low-budget exploitation films became known as grindhouse movies in the 70s. The genres were varied but they typically included some sort of taboo subject matter. Some films would contain explicit violence while others focused on nudity and sex. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre contains neither, but its title alone gave it a place right alongside the 70s Mondo boom.

Tobe Hooper began outlining his ideas for a horror movie in the early 70s but the film was never meant to be an exploitation flick. Hooper even tried to get the film a PG rating. An effort that the MPAA scoffed at with their hard R designation. But his film, what would eventually become The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, wasn’t really about chainsaws. It was about meat and being lied to.

How The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Softens its Violence

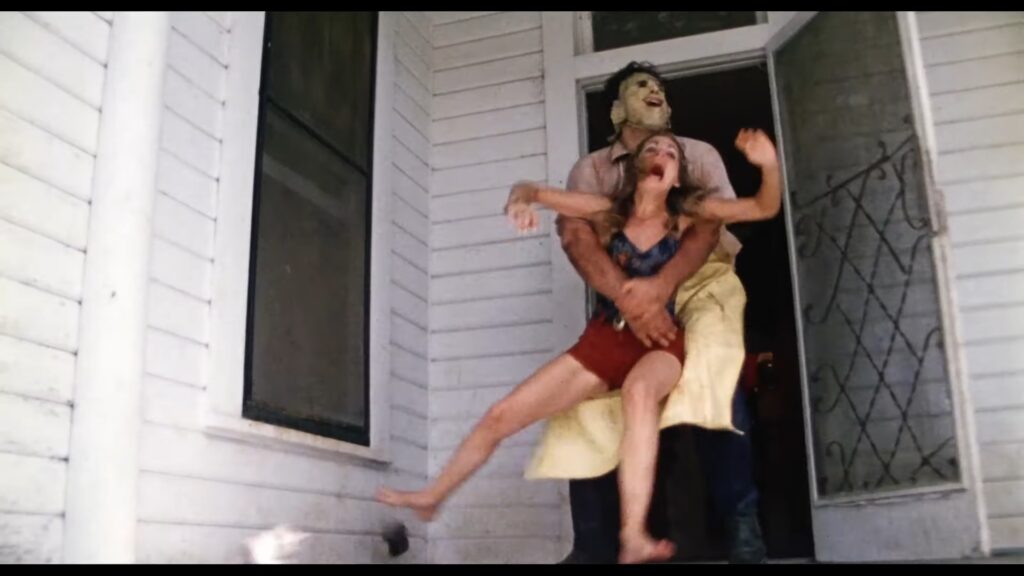

Throughout the film The Texas Chainsaw Massacre there is a sense of dread and terror around every corner. The title of the film and the opening scrawl promise a brutal and bloody film. But The Texas Chainsaw Massacre never delivers on these promises. There are kills, severe ones, but the camera does an interesting trick. It uses the actors to block the violence. When a woman is impaled onto a meathook, her torso hides the entry. When Franklin, a wheelchair-bound young man, is slain with a chainsaw, his body blocks all the violence. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is able to use the victims of violence, as a shield to the actual violence happening on screen.

Building on this, the violence in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is truthfully quite mild. For a film with Chainsaw Massacre in the title, there is really only one image of a chainsaw going through flesh. And this is a self-inflicted leg wound. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre commonly gets lumped together with the violent exploration films of the 70s but it doesn’t share a lot of the same DNA. There are attractive women, but they remain clothed throughout. There is brutal violence but it all happens outside of the audience’s view. And there is a psycho killer but he never gets his revenge or comeuppance.

Holding a Mirror to the Media

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a film that is very much in conversation with the media of the time. A surge of serial killers, real and make-believe, led to a boom in sensational media. combined with the Watergate scandal and headlines made to engage readers, news had started to become the money-making entity we see it as today. Tobe Hooper wanted to toy with this notion and he wanted to lie to his audience. He marketed the film as a “true story” knowing that audiences would more often than not take his word for it. What people expected, a bloody violent chainsaw romp, is far from what audiences received.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre lays its themes on thick. The big bads of the film are a family of deranged out-of-work slaughterhouse butchers. Throughout the beginning of the film, the presence of slaughterhouses is made known while a group of unsuspecting teens drive through Texas. At first, it seems like nothing more than a strange backdrop. It’s merely Dialogue used to fill out the script and clear any dead air. But once the teens enter the farmhouse of horror, it becomes clear Slaughterhouses aren’t just scene settings. It’s the entire point of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Going Vegan

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre may not be a film about giving up on animal products as PETA would like to suggest. But it is a film starkly obsessed with meat. The victims in the film are used for their meat. The deranged killers slice them up with a chainsaw and cook them into BBQ. They promise to use every part of the meat, even the heads, but this provides little solace to the victims being sourced for their meat. The teenagers are helpless, just like animals, and the fear in their eyes perfectly emulates the fear of those who are slaughtered.

Towards the end of the film at the infamous dinner scene, the camera work used to capture Marilyn Burns is astounding. The camera trains in closer to her pupils with each quick cut. Every time the camera cuts back we are closer to her eyeball. We see her eyes dart back and forth as she helplessly tries to understand her situation. It’s a startling image even today that brilliantly captures slaughterhouse victims in a way few films have. We see her eyes as that of a cow or a sheep. Just waiting for the slaughter. Unaware of what or why this is happening to her, but terrified all the same.

The Legacy of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

50 years ago The Texas Chainsaw Massacre changed cinema. Better horror movies had come out before, and better ones would be released later, but The Texas Chainsaw Massacre did something few films have been able to. It tricked an audience and defined an era.

Tobe Hooper’s 1974 film isn’t a masterpiece for what it did, but rather for what it didn’t. It hid the violence but still felt brutal. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre masks the killer and makes him even more terrifying. And the film ends with no resolution. The final girl escapes in a truck, the psychotic Leatherface in pursuit, but the final moment is a stark cut between screams and chainsaw revving. Few films leave you feeling as unsettled as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s ending. It’s an ending that sticks long after the final cut, making you ponder what you’ve just witnessed. The longer you contemplate the deeper the film gets. That’s why we are still talking about The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 50 years later.